06_2018

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

L’ambiguïté de la machine

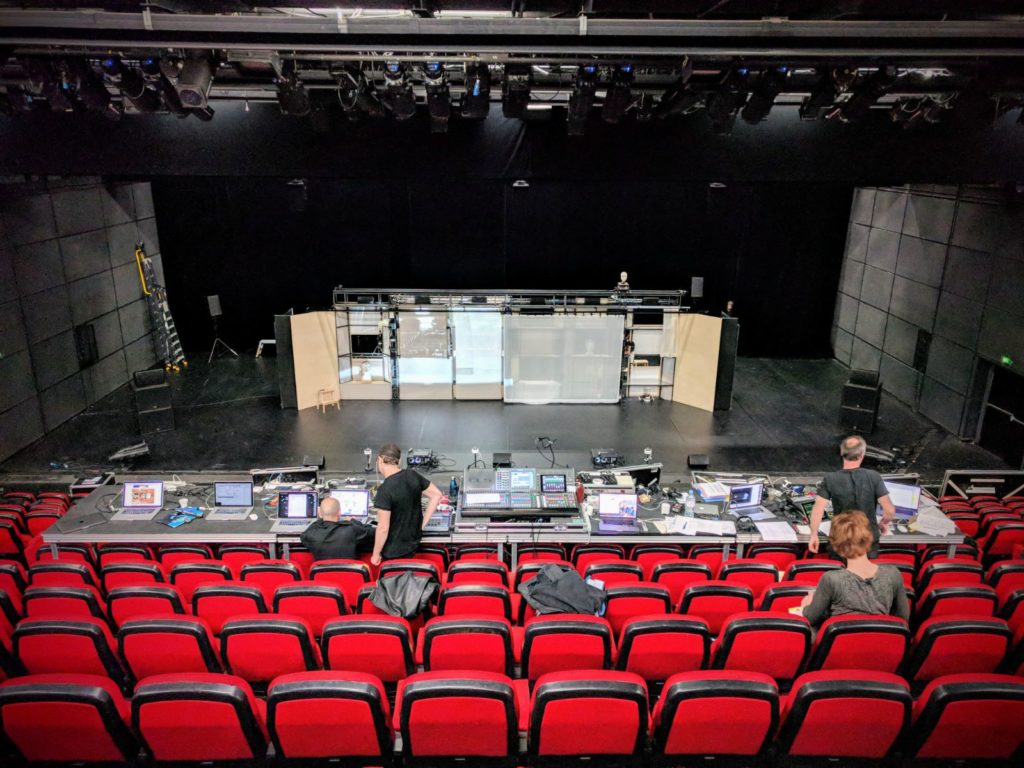

Interview avec Olivier Pasquet à l’occasion de la création les 6 et 7 juin 2018 au Centre Pompidou.

Vous êtes le premier RIM avec lequel Georges Aperghis a travaillé à l’Ircam, sur rien moins que Machinations et vous remettez le couvert aujourd’hui pour Thinking Things : avez-vous remarqué une évolution dans son approche de l’informatique musicale ?

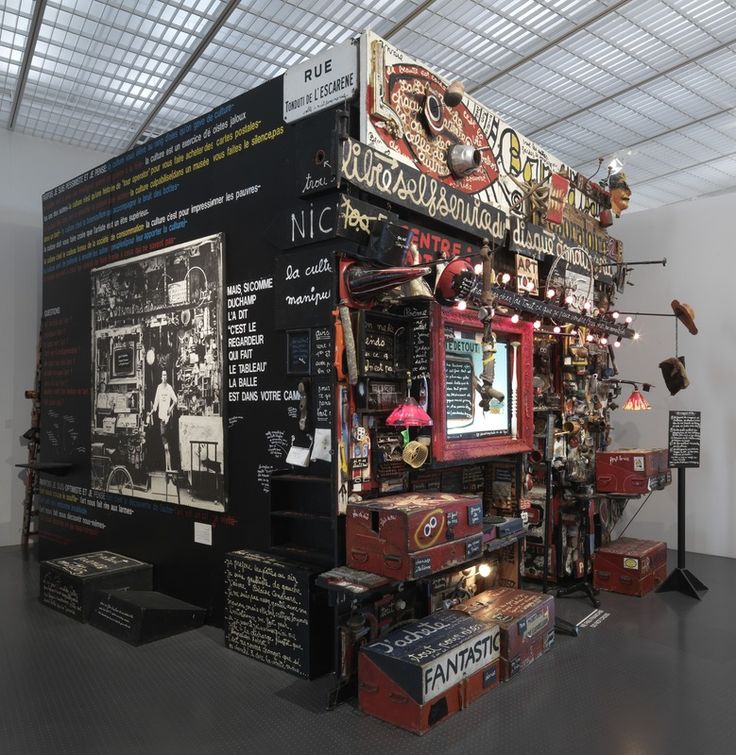

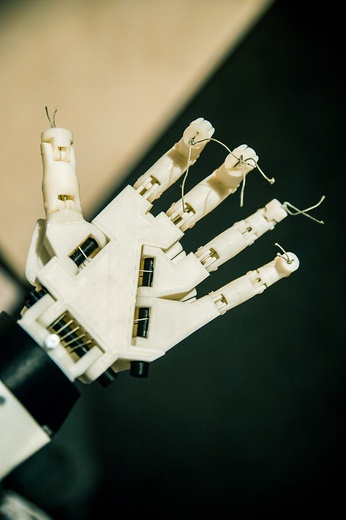

Olivier Pasquet : Machinations était son premier projet avec l’Ircam. Je suppose donc que le sujet du rapport entre l’homme et la machine est apparu naturellement. Dix-huit années plus tard, au fil des pièces, Georges a autant avancé dans sa recherche artistique que le rapport de la société à la technologie. Les deux se sont fondus au point qu’on ne parle plus vraiment de rapport mais d’intégration à un niveau sociétal plutôt qu’uniquement organologique. Le microprocesseur ne se définit plus uniquement comme une machine universelle qui déplace et transforme de l’information, de la matière. On a décidé de l’intégrer dans nos pensées, faits et gestes — parfois comme un régulateur. Ici, Georges va un cran plus loin et parle de l’assimilation humaine de l’outil, qui devient littéralement une extension des membres. Dans le spectacle, cette mécanique devient automatique et autonome. C’est selon moi la raison pour laquelle le travail scénique et musical de la pièce mélange les corps et voix des chanteurs avec des robots. La confrontation entre la machine et l’humain de Machinations a été transposée.

La pièce regorge de mécanismes et de mécaniques. Elle force les comédiens/chanteurs à penser, à formaliser d’une façon unique et à jouer comme elle. Les questions posées, s’ils elles doivent exister, sont donc peut-être plus systémiques. Dans Machinations, l’homme explorait les confinements de cette relation comme les règles d’un jeu. Dans cette nouvelle pièce, il reste toujours un rapport de domination mais celui-ci s’est inversé.

La « machine » en tant que telle est une préoccupation centrale de cette nouvelle pièce : comment cela change-t-il son appréhension et sa gestion ?

Machinations jouait avec les artefacts de la machine par le biais de clics numériques, de saturations etc. L’artificiel est toujours présent dans la pièce puisque l’œuvre est, par définition, toujours artificielle dès lors qu’on se place du point de vue de celui qui la crée. Ici, toutefois, le réalisme de Thinking Things se situe totalement dans le factice, le truqué.

Par exemple, la partie électronique emmêle des « vraies » voix et des voix complètement synthétiques. Celles-ci sont utilisées lorsqu’il s’agit d’aller au-delà de ce que peut la voix humaine. Ce sont parfois des extensions humaines, parfois des personnages à part entière. Ces synthèses, ces apparents artifices, sont importants à mes yeux. Leur niveau totalement subjectif de réalisme, et l’intérêt qu’on lui accorde, constitue un « romantisme » où l’artifice acquiert le statut de « nature artificielle ». Il y a autant, voire plus, de natures artificielles que l’on peut en imaginer. La pièce elle-même, et ce qu’en perçoit le public, en sont deux.

L’esprit et le formel imposés sont plus présents et complexes que dans Machinations. La partie électronique le démontre aussi en utilisant à la fois quelques processus compositionnels et des micro-montages manuels. Cette complexité émergente, faite d’entrelacements et d’interactions entre des choses simples, engendre une esthétique granulaire dans laquelle des ornements baroques infinitésimaux se confondent avec un objet plus substantiel. Il en résulte une ambiguïté flagrante entre une série de micro-mécanismes, la part de leur action à l’échelle de la pièce et finalement le spectacle, vivant.

Lorsqu’on songe au titre, « Thinking Things », on ne peut pas ne pas penser à l’intelligence artificielle : si le concept nourrit sans doute la réflexion artistique, qu’en est-il de la technique ?

La pièce n’utilise pas « réellement » d’intelligence artificielle. Georges a écrit quelques parties de la pièce avant les répétitions. Un tel déterminisme n’a nul besoin d’une telle approche dynamique en amont ou dans le temps réel cette performance. Si on considère l’intelligence artificielle comme un outil, les questions de son utilisation dans un spectacle es sont exactement les mêmes que pour le temps-réel. Pour donner un exemple concret : généraliser ou rendre autonome un processus compositionnel pour une pièce traditionnellement lue de façon linéaire par le public aurait-il un sens ? Je pense que oui, du point de vue du compositeur. Le choix d’une échelle de contrôle, des diverses synchronicités et du déterminisme formel sont pour lui des questions cruciales, qui sont profondément liées à des choix culturels et esthétiques. Nous avons donc affaire à une intelligence tout court ; une machine ambiguë faite de diverses natures dans d’autres natures ; d’un corpuscule dont on comprend au fil du temps de la pièce qu’il n’est qu’un système.

Propos recueillis par Jérémie Szpirglas.

J’ai donc commencé à l’Ircam avec Machinations et il est fort probable que je termine avec Thinking Things.

Pour expliquer brièvement un certain contexte, je me permets de partager ici une anecdote. Considéré comme un technicien, la production de l’Ircam refusait de me loger au début. J’ai du m’arranger avec des amis, sauter d’un canapé à un autre, dormir dans la baignoire de l’ingenieur du son du projet. Au fil des mois, voire des années, j’ai réussi à avoir un airbnb à chaque fois que je venais travailler à l’Ircam pour cette pièce. Malheureusement, ces appartements parisiens sont tellement insalubres que j’ai attrapé des puces, me suis brûlé sous la douche etc etc. Georges Aperghis a eu l’extrême gentilesse de me loger par la suite jusqu’aux dernières representations au Centre Pompidou. Ceci et tous les à-côtés non cités ici créent des situations qu’on n’oublie pas.

———————————————————

Google translate for now:

Ambiguity from the machine

Interview with Olivier Pasquet for the creation on June 6 and 7 2018 at Centre Pompidou, Paris.

You are the first to collaborate with Georges Aperghis at IRCAM, on nothing less than Machinations and you cover up today for Thinking Things: Have you noticed an evolution in his approach to computer music?

Olivier Pasquet: Machinations was his first project with IRCAM. I suppose then that the subject of the relation between man and machine appeared naturally. Eighteen years later, as the plays progressed, Georges made as much progress in his artistic research as the company’s relationship to technology. The two have merged to the point that we do not really talk about relationships but integration at a societal level rather than just organological. The microprocessor is no longer defined simply as a universal machine that moves and transforms information and matter. We decided to integrate it into our thoughts, actions, and gestures – sometimes as a regulator. Here, George goes a step further and talks about the human assimilation of the tool, which becomes an extension of the members. In the show, this mechanics becomes automatic and autonomous. In my opinion, this is why the stage and musical work of the piece mixes the bodies and voices of the singers with robots. The confrontation between the machine and the human of Machinations has been transposed.

The room is full of mechanisms and mechanics. It forces comedians/singers to think, to formalize uniquely, and to play like her. The questions asked, if they must exist, maybe more systemic. In Machinations, the man explored the confinements of this relationship as the rules of a game. In this new piece, there is still a relationship of domination but this one has reversed.

The “machine” as such is a central concern of this new piece: how does this change his apprehension and management?

Machinations played with machine artifacts through digital clicks, saturations, and so on. The artificial is always present in the room since the work is, by definition, always artificial from the point of view of the one who creates it. Here, however, the realism of Thinking Things is totally fake, the rigged.

For example, the electronic part entangles “real” voices and completely synthetic voices. These are used when it comes to going beyond what the human voice can. They are sometimes human extensions, sometimes characters in their own right. These syntheses, these apparent artifices, are important to me. Their totally subjective level of realism, and the interest given to it, constitutes a “romanticism” in which artifice acquires the status of “artificial nature”. There are as many, if not more, artificial natures as one can imagine. The piece itself, and what the public perceives, are two.

The imposed mind and formal are more present and complex than in Machinations. The electronic part also demonstrates this by using both some compositional processes and manual micro-assemblies. This emergent complexity, made of intertwining interactions between simple things, generates a granular aesthetic in which barely infinitesimal ornaments merge with a more substantial object. The result is a blatant ambiguity between a series of micro-mechanisms, the part of their action at the scale of the piece, and finally the show, alive.

When one thinks of the title, “Thinking Things”, one can not but think about artificial intelligence: if the concept undoubtedly feeds the artistic reflection, what about the technique?

The room does not use “real” artificial intelligence. Georges wrote some parts of the piece before the rehearsals. Such a determinism does not need such a dynamic approach upstream or in real-time this performance. If we consider artificial intelligence as a tool, the questions of its use in a show are exactly the same as for real-time. To give a concrete example: generalize or make autonomous a compositional process for a piece traditionally read linearly by the public would it make sense? I think so, from the point of view of the composer. The choice of a control scale, various synchronicities, and formal determinism are for him crucial questions, which are deeply linked to cultural and aesthetic choices. We are therefore dealing with a simple intelligence; an ambiguous machine made of different natures in other natures; of a corpuscle which one understands over time of the piece that it is only a system.

Interviwed by Jérémie Szpirglas.

I started at Ircam with Machinations and there are great chances I end with Thinking Things.

To briefly explain a certain context, I would like to share an anecdote here. Considered a technician, the Ircam production refused to give me lodging at the beginning. I had to make arrangements with friends, jump from one couch to another, and sleep in the bathtub of the sound engineer of the project. Over the months, even years, I managed to get an Airbnb every time I came to work at Ircam for this piece. Unfortunately, these Parisian apartments are so unhealthy that I caught fleas, burned myself in the shower, etc. Georges Aperghis was kind enough to put me up until the last performances at Centre Pompidou. This and all the other sides not mentioned here create situations that are not forgotten.